The remains of Missouri’s mining history are, at times, unrecognizable.

In west-central Missouri’s Henry County, there are parts of a 107-acre property that are patchy, rocky and hostile to plants. Just down the gravel road, though, several sites feature big blue stem, clover and other lush vegetation. All these plots are in the town of Montrose and were similarly mined then abandoned generations ago. They’re just in different phases of healing.

Across the state, scars from years of unregulated coal and lead mining are being mended. Two factors largely contribute to land restoration: work by state and federal agencies and time for nature to take its course.

“After so many years, it’s hard to tell post-reclamation versus somebody’s farm right next door,” said Austin Rehagen, an environmental specialist at the Missouri Department of Natural Resources.

Since the mid-19th century, the mining industry periodically peaked in parts of the state. With booms in coal and lead mining but no laws to govern how mined land was treated, companies often abandoned sites without repairing the damage they had done.

About 67,000 acres of unreclaimed land were left behind from coal mining, and another 40,000 from companies that mined for other metals, according to the DNR’s 2020-2021 biennial report.

The federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, passed in 1977, requires that mining companies meet specific standards for restoring land mined after that year. But previous mining left behind centuries-old lead mine shafts, acid mine drainage, barren land and steep highwalls, among other hazards.

Austin Rehagen, environmental specialist at the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, walks on barren ground at a former mine site on July 21. Companies that mined land before 1977 often removed needed layers in the land’s soil profile and failed to save them for eventual restoration. The absence of topsoil makes it difficult for plant life to grow.

In recent decades, agencies have stepped in to address the public and environmental risks some abandoned mine sites present. Although some Missourians are familiar with the state’s Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation Program and the legislation that governs it, the actual processes of the department, and others that reclaim mine land, are a bit more complex.

Agencies involved in reclamation

Projects are typically overseen by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources’ abandoned mine land program and Region 7 of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which is responsible for sites in Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska and nine tribal nations.

The EPA generally leads the cleanup phase for Missouri’s Superfund sites, those contaminated by the release of hazardous wastes or substances, Shannan Beisser, lead press officer for Region 7, wrote in an email. Mining hazards aren’t the only producers of Superfund sites; manufacturing facilities, processing plants and landfills are a few other examples.

“In order to qualify for addition to the Superfund National Priorities List (NPL), a site must be determined to exceed a specific threshold of actual or potential risk to human health and the environment,” the email read.

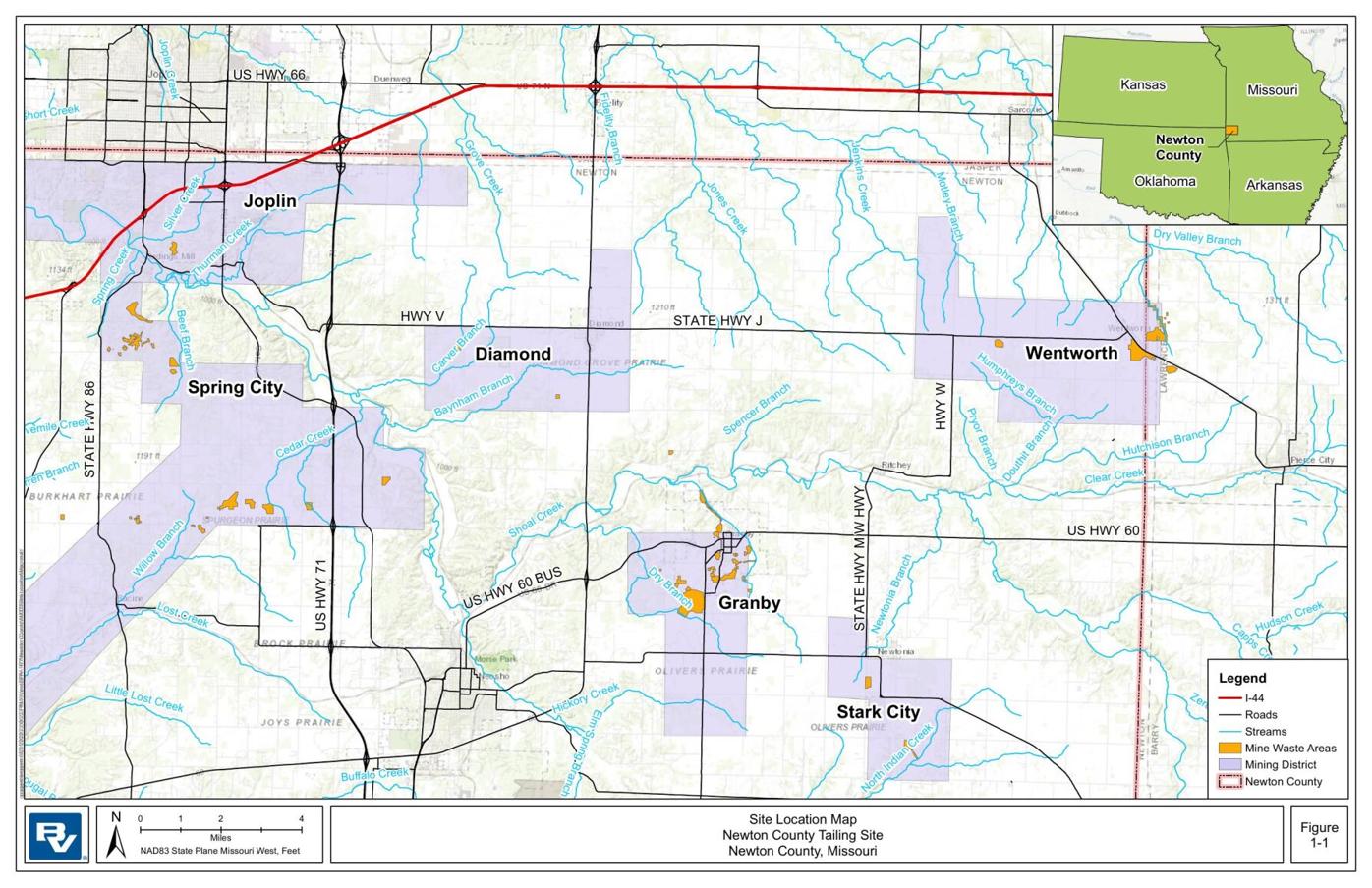

The EPA has done cleanups in the Tri-State Mining District, composed of Missouri and parts of Kansas and Oklahoma, where lead and zinc were milled and smelted for over a century.

“EPA Region 7 has cleaned up over 27,000 residential properties and over 40 million cubic yards of mine waste so far,” Beisser wrote. Most of that cleanup was done in Missouri.

Superfund cleanups consist of heavy construction, said Elizabeth Hagenmaier, project manager of a Superfund site in Newton County. At mine waste areas, contaminated soil and mine waste are dug up and transported off site.

A difference between the two agencies is that the Missouri DNR must prioritize sites that threaten human safety while the EPA is permitted to tackle environmental hazards, Rehagen said.

Sites are ranked by priority of hazard. Priority 1 and 2 locations present threats to public health and safety, whereas Priority 3 locations are more environmental concerns. The state DNR’s Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation program is required to start with Priority 1 locations as they arise. Then, it can focus on Priority 2 locations, and eventually, Priority 3.

Iron stains the soil and water at an abandoned mine pit off Route 52 on July 21 in Montrose.

The program’s long-term projects are often coal-mining related, but it still addresses Priority 1 lead/zinc mine shafts. For the state program, coal projects include earth-moving and land-management projects. Abandoned shafts from lead/zinc mining are filled or closed with cement, and the department addresses other immediate hazards.

Shafts are addressed on an as-needed basis and as locations are reported to the team, Rehagen said.

Suzy Rhine of Joplin got in touch with the DNR one day last spring after she came in from mowing the lawn and heard a huge crash.

“It sounded like if a garage door were all the way up and they just let it loose and hit the ground,” she said. Then, she heard water running under her house.

What Rhine initially thought was a plumbing problem turned out to be a lead/zinc mine shaft that dropped out below her house. It was about 40 feet deep, she said.

The DNR put Rhine in touch with its abandoned mine land reclamation program. Days later, when they arrived, she learned there was a number of similar abandoned sites in the area. The shaft was later filled, and Rhine said she feels much safer.

“Now I really feel like I have one of the safest houses in the whole area,” Rhine said.

The mine reclamation program’s total inventory of unfunded, uncompleted projects for Priority 1, 2 and 3 sites statewide adds up to about 10,800 acres that would cost roughly $123.2 million to reclaim, Rehagen said. The inventory is ever-evolving and constantly updated as projects are added. At this time, the program runs on a budget of roughly $2.8 million per fiscal year, Rehagen said. Revenue from a tax on coal production, per ton, pays for the reclamation projects.

The DNR has nine large abandoned coal projects in varying design and contracting phases. One is under construction. Rehagen said the department plans to have four sites in the construction phase by the end of the year.

Acid mine drainage

Acid mine drainage, the natural movement of acidic water concentrated with heavy metals, can present a number of public and environmental problems such as acidic water bodies and dangerous highwalls.

In the days of pre-1977 mining, companies rarely stockpiled the necessary layers of the soil profile that were dug out when land was mined. Because the layers above the coal seam were not saved and reinserted, barren, rocky land — susceptible to runoff — took its place.

Austin Rehagen, environmental specialist at the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, holds up a chunk of shale at an abandoned former mine on July 21 in Montrose. Shale is a sedimentary rock that forms when different minerals are compressed over time.

“It looks kind of like a moonscape in some areas,” Rehagen said.

Often, when coal spoils and mining remains are left on top of the soil, rain can mix with the minerals to create runoff tainted with acid, which in turn can steepen highwalls along the edges of pits.

Due to the absence of topsoil, vegetation is typically sparse. Without erosion control, runoff can make the walls so steep that they become hazardous. A driver veering off a roadside next to a highwall would risk serious injury.

To address this issue, the ground surrounding the highwall is evened out to reduce the steepness of the slope. Remaining coal spoils can be buried or used to fill the land, Rehagen said. A steep highwall off a dusty gravel road in Henry County is in the design phase for construction. Once that’s done, the site will be limed, fertilized and seeded with wheat, oats or rye to control erosion. The department often uses agricultural lime, an additive made from crushed limestone that reduces soil acidity and enhances fertilization.

Runoff can also pool up in leftover mining pits, creating acidic ponds. The size and depth of the pond can often determine its acidic concentration.

“Dilution is the solution to pollution,” Rehagen said, explaining that the higher the volume of “good water,” the less acidic concentration water bodies will have.

Acidic water is most recognizable by a reddish tint due to its low pH and high iron concentration, but it can also appear quite clear at times. Pyrite or iron sulfide are both mining residuals. These minerals release iron in the presence of water and oxygen, which reduces the pH of the water. Low pH water then produces sulfuric acid. Highly acidic pits, with a pH of 3.5 for example, rarely sustain any plant or animal life.

Pits that are large enough can be treated with hydrated lime, crushed limestone mixed with water. The soluble mixture increases the water’s pH.

The program also uses a passive treatment system to address acid mine drainage, which it calls an OLA cell. OLA, an Organic Lime and Alkalinity treatment, requires little maintenance. Rather than daily upkeep, Rehagen said, they’re checked only periodically.

Crews begin by installing geotextile fabric and perforated pipes at the bottom of a shallow pond. Then, the team adds in layers of limestone, mulch and organic compost, mixed in with agricultural lime. When acid mine drainage seeps into the pond, head pressure vertically pulls it down through all the layers of materials, adding alkalinity. The water is pulled into the pipe then flows downstream to a polishing or wetland cell.

“It’s pretty much just adding organics, those microbes, into the system and then also adding alkalinity to that acid water,” Rehagen said.

The water will be transported to another cell if needed. From there, the final cell retains the treated water until it moves to a large pit or runs off the property.

“It gives it a chance for the water to clean up before leaving those cells,” Rehagen said.

Lead-contaminated water supplies

The EPA has been investigating and cleaning up contamination from mine waste areas around Newton County since 1986, according to the EPA’s webpage on the Newton County Mine Tailings Superfund site. The sites are part of the Tri-State Mining District.

Near Granby, the Missouri DNR and the EPA confirmed and investigated increased concentrations of lead, cadmium and zinc in the soil and groundwater in the 1980s and 1990s. Not long after, in 1995, elevated lead levels were found in a Spring City child’s blood. This resulted in an assessment of soil and drinking wells across Spring City. These are two examples of a number of hazards existing in the county.

“Past mining and milling practices have resulted in contamination of surface soil, sediments, surface water and groundwater in the shallow aquifer,” Beisser’s email read.

In 1998, the EPA began offering bottled water to some Newton County residents due to the number of private drinking wells heavily contaminated with lead and cadmium. New water supply systems were built to replace the contaminated wells.

About 100 deep-aquifer drinking wells have been installed, according to the EPA site. Lead-contaminated soil was removed from about 300 properties in Diamond, Spring City and Granby mine waste areas combined. Remediation of mine waste areas across the county is ongoing.

Beisser’s email explained that mine waste and contaminated soil are moved to and stored in repositories constructed on upland mine waste piles. Repositories are located at higher elevations to avoid floodplains, Hagenmaier said. She has been a project manager at the EPA for 11 years and has worked on the Newton County site since 2014.

Cleanup and ongoing efforts to address contaminants in the county could take decades to complete, Hagenmaier said.

Plant and animal life

After mine land has been recovered and immediate hazards are resolved, the Missouri DNR tries to address some of the environmental problems at reclaimed sites. This includes restoring plant life on barren, acidic land.

It can take one, two or even three years to successfully revegetate on top of acidic materials that lack topsoil, Rehagen said.

“It’s not like planting a garden where you just get up and you plant and everything grows with very little amendments,” he said. “We’re starting from ground zero, where there’s a lot of shale.”

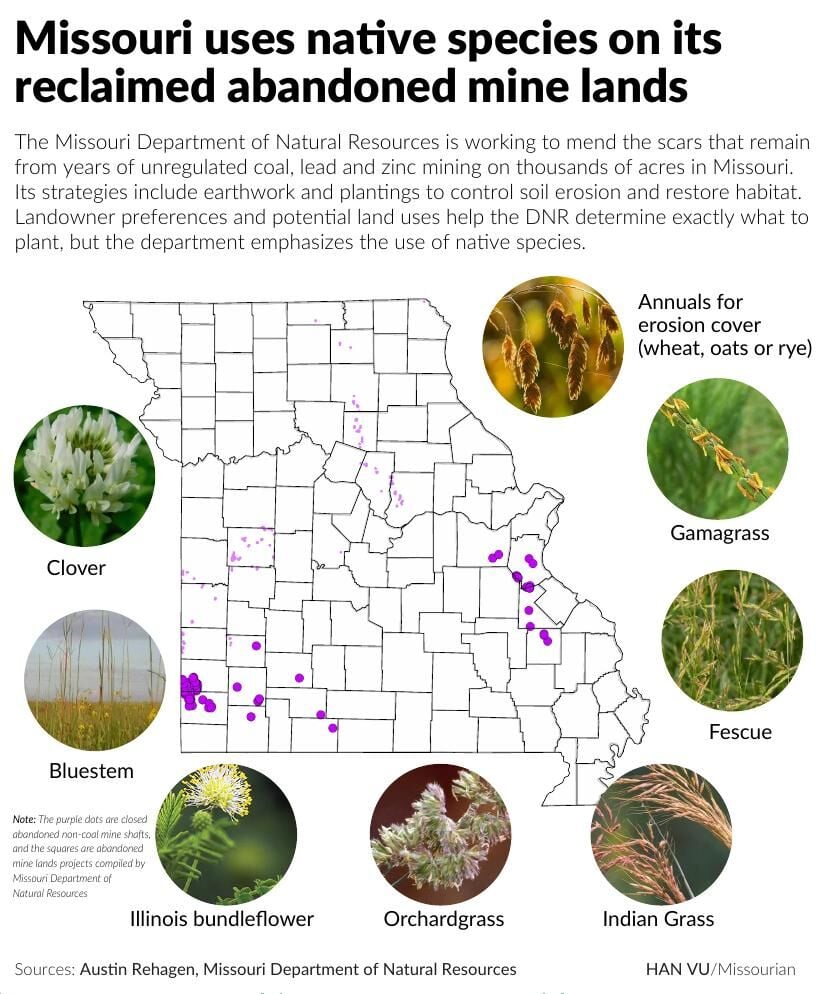

The intended use for the land and private landowners’ personal preferences determine what species of plants go in the ground. If it’s meant to be pasture land, the reclamation team will plant a grass mix. If someone wants to create habitat for wildlife or pollinators, they’ll plant warm-season plants such as milkweed or Illinois bundleflower. Regardless of intended land use, the department plants annuals such as wheat, oat and rye for erosion control, ground cover and stability.

Alfalfa, bluestem and orchardgrass are just a handful of the department’s “go-to” reclamation planters.

The department tries to promote native, economical crops, Rehagen said.

“Either way, private or public, as far as like conservation land or private individual, we always stress native species,” he said. After this growth period, the landowner is able to continue to use the land as they’d like.

Although the agency plays a role in replanting, vegetation on some abandoned mine land has returned naturally.

“Time is our friend on a lot of these sites,” Rehagen said. Some land, untouched for years, has grown on its own in some areas. In others, patchy barren land is an indicator of heavy acidity and lackluster growth.

Occasionally, the department will plant trees after reclamation as a reforestation effort, Rehagen said. He added that the department will typically reach out to the community and offers planting as a volunteer opportunity for local high schoolers in 4-H and FFA.

Residents often report seeing more deer and turkey after land is reclaimed, Rehagen said. He added that grasslands might make it easier to see animals when the land is evened out. He also said the resources the restored land provides may draw animals in.

“The animals need a mixture of habitat, water and food,” he said. “And if they have that, I think even though they’re temporarily displaced during the construction, they normally come right back and use the area.”

A plot of land that was reclaimed in January 2021 near Appleton City.